The Brand Awareness ‘Awareness’ Conundrum

This Week: An Anonymous CMO shares how brand awareness is often misunderstood and leads to CMOs having short tenures and more. 🧃

CMOs Anonymous is insider intel for Australia’s future CMOs. You can listen to first episode of CMOs Anonymous where Top 50 CMO Steffen Daleng explains how you can get customers to BUILD THE BRAND FOR YOU…

Podcast aside, CMO Anonymous is sharing insights on brand awareness below:

“You would think, after all this time, there would be a body of evidence articulating the value of Brand Awareness metrics and which metric, under which conditions, you should monitor. Unfortunately, this is not the case.” — Jenni Romaniuk.

The greatest trick the Marketing Devil ever played was to give marketers what they wanted: soaring levels of Brand Awareness for, well, Brand Awareness.

In cluing colleagues in on our branding lingo we got the buy-in we wanted, but we weren't careful what we wished for. A branding industry built on traditional Brand Awareness metrics might be the root of all marketing’s biggest problems — low CMO tenures, interdepartmental turf wars, and a branding industry that’s veering away from ‘brand’ altogether.

Brand Awareness is a metric known by every department from IT to HR to QA. And they all agree it's worthy of real estate on company-wide dashboards. After all, it's such a simple metric. So basic and professionally prosaic that to explain its value risks patronisation.

And therein lies the rub.

We don't explain it because we figure everyone understands it (of course they do! 'Simple! 'Basic!' etc). But when comprehension is taken for granted we fail to interrogate our own understanding, our knowledge falls off the face of a cliff, and voila: familiarity heuristic.

It’s very possible that in taking for granted this little, foundational metric we’ve set up a house of cards. We’ve based campaign funnels on a seeming no-brainer, but failed to inspect what researchers have been telling us for years — our use of Brand Awareness as a metric is deeply flawed.

In partnership with Lemonly

Visual storytelling by Lemonly: Custom infographics, animated videos, and microsites for B2B brands

Don’t let confusion cloud your content. Leverage the power of visual storytelling to make your message memorable and your data digestible.

That’s Lemonly’s specialty—creating delightful infographics, animated explainer videos, microsites, and other visual content for the world’s best brands. They’ll bring clarity, personality, and polish to all your brand’s content.

With 5,000+ projects created for clients in B2B technology, healthcare, tourism, and more, the Lemonly team are experts in illustration, data visualization, and motion graphics. See why brands like Marriott, AMD, HealthStream, and Activision Blizzard trust Lemonly to tell their stories.

Talk with Lemonly about partnering for your next visual content project.

Brand Awareness and the Illusion of Explanatory Depth

I hate to pull a Gladwell, but to explain why CMOs might be bad at explaining Brand Awareness, and might not even understand it, I need to sidestep into a niche-but-interesting case study from academia. Bear with me.

In reaching near 100% saturation levels of Brand Awareness awareness we've created what cognitive scientists call the illusion of explanatory depth (IoED). Not to be confused with the Dunning-Kruger, this bias occurs when we hand-on-heart believe that we understand the nuances of a simple topic when that ‘understanding’ exists only in the minds of others.

In reality, we couldn't explain it if we tried.

Yale psychology professor Frank Keil first thought of IoED when, ironically, it came to him in a eureka moment in the shower and he had to rush into work to explain it to his collaborator Leon Rozenblit.

Their subsequent 2002 paper on IoED gave us a three-question method for disinfecting ignorance with sunlight.

In their surveys, they asked a set of questions like those below.

1. On a scale from one to seven, how well do you understand how zippers work?

2. How does a zipper work? Describe in as much detail as possible all the steps available in a zipper's operation.

After participants completed the second question to the best of their understanding they were given the last part of the test:

3. Now, on the same one to seven scale, rate your knowledge of how a zipper works again. Take a moment to consider that, but for Brand Awareness instead of zippers.

How many people in your marketing team would answer the first question with a number lower than six? How many might fail to qualify their rating and then change their score in the final question?

Visual learners can consider example from The Knowledge Illusion, a book by the cognitive scientist Steven Sloman and marketing professor Philip Fernbach.

"A telling example of the illusion of explanatory depth can be found in what people know of bicycles. Rebecca Lawson, a psychologist at the University of Liverpool, showed a group of psychology undergraduates a schematic drawing of a bicycle that was missing several parts of the frame […]”

“She then asked the students to fill in its missing parts."

If, like me, you failed and by trying something like the top left, don't feel too bad. Lawson tested 68 cycling ‘experts’ and not even they scored perfectly.

CMO Tenures Explained Away

So I didn't know where the chain connected. So what? I can still ride a bike. Failing to understand electricity doesn't stop my light from turning on, and an incomplete understanding of how Brand Awareness doesn't stop ads from cluing customers onto brands.

Does it matter? If it didn’t, we wouldn’t work in a profession where Boathouse data shows 52% of America’s top B2C CEOs think CMOs choose to speak “their own language” instead of “the language of the business”.

In 2024 the average CMO tenure at top advertisers is a scary 3.1 years. That's not only leagues less than other C-suites, it's barely enough time for a brand campaign to affect share-of-market and put brand on the balance sheet.

That omission from fiscal reports can lead large listed firms to focus on short-term 'performance' media to meet quarterly earnings season targets. When senior marketers were surveyed on burning issues at Cannes Lions in 2022, twice as many cited "managing the tension between brand and performance marketing" than any other challenge.

And that sentiment has endured. Nielsen's 2024 Annual Marketing Report showed that 70% of marketers intended to spend less on brand building and more on performance media.

We have a veritable litany of research and data to prove long-term value of brand building. You’ll barely make it out of an agency pitch without seeing graphs from Peter Field and Les Binet.

If CMOs have the data to make the case why the hell would so many companies be cutting brand spend in favour of less efficient advertising?

It’s shortsighted to think the fault lies in CEO myopia. If CEOs don’t understand brand measurement it’s because CMOs aren’t communicating it clearly. Likely, because CMOs don’t know how.

Brand Awareness Explained in Depth

If you tried to explain Brand Awareness in all its detail and said it has a top-of-funnel function that leads to 'Consideration' and is measured with CPM, you might be part of the problem.

To explain why, I scoured research papers over the decades but found no better explanation than from Jenni Romaniuk — the famed marketing researcher from Ehrenberg-Bass. Unlike me she is one of the few marketing researchers in the world who can explain Brand Awareness in excruciating detail.

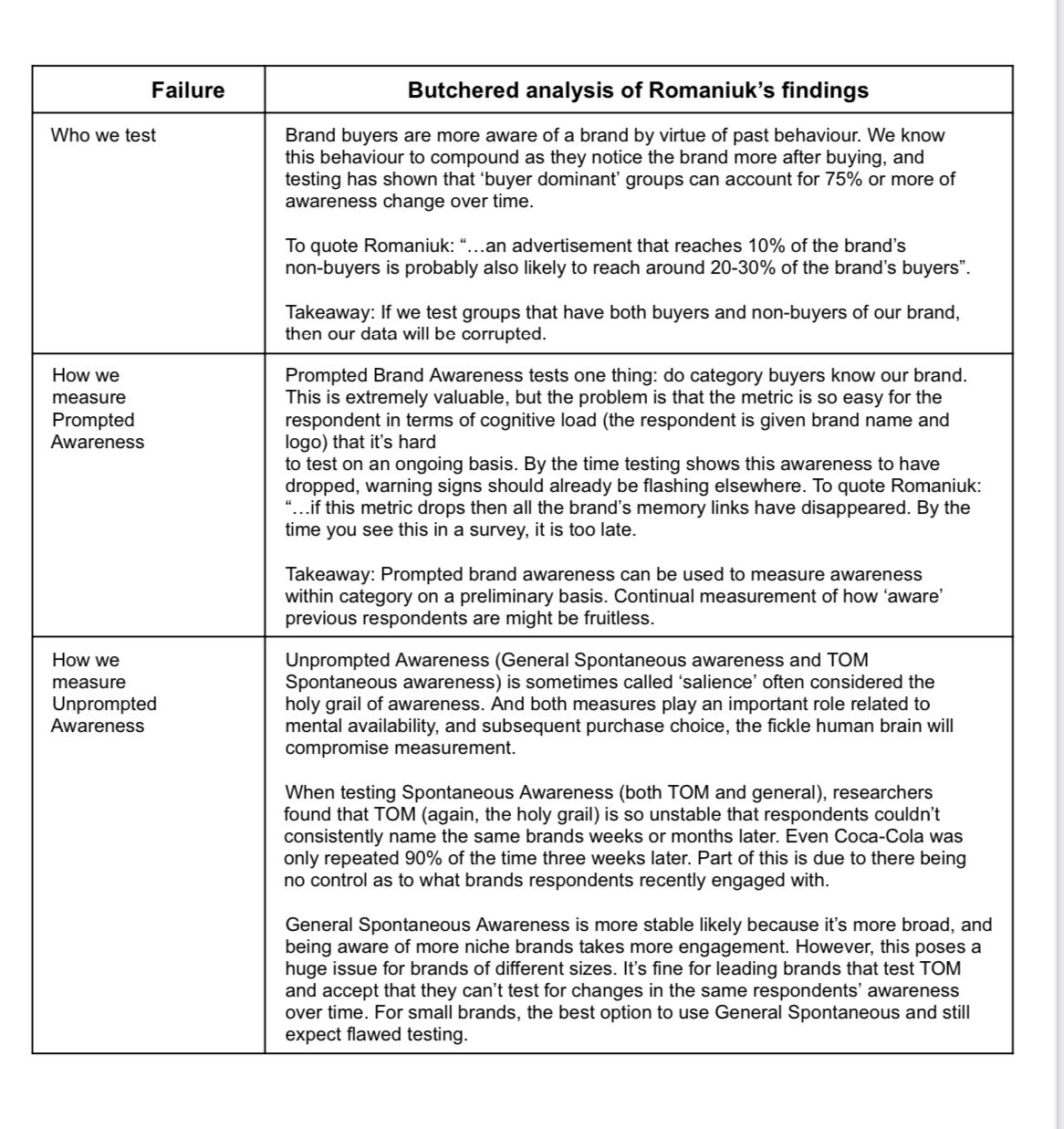

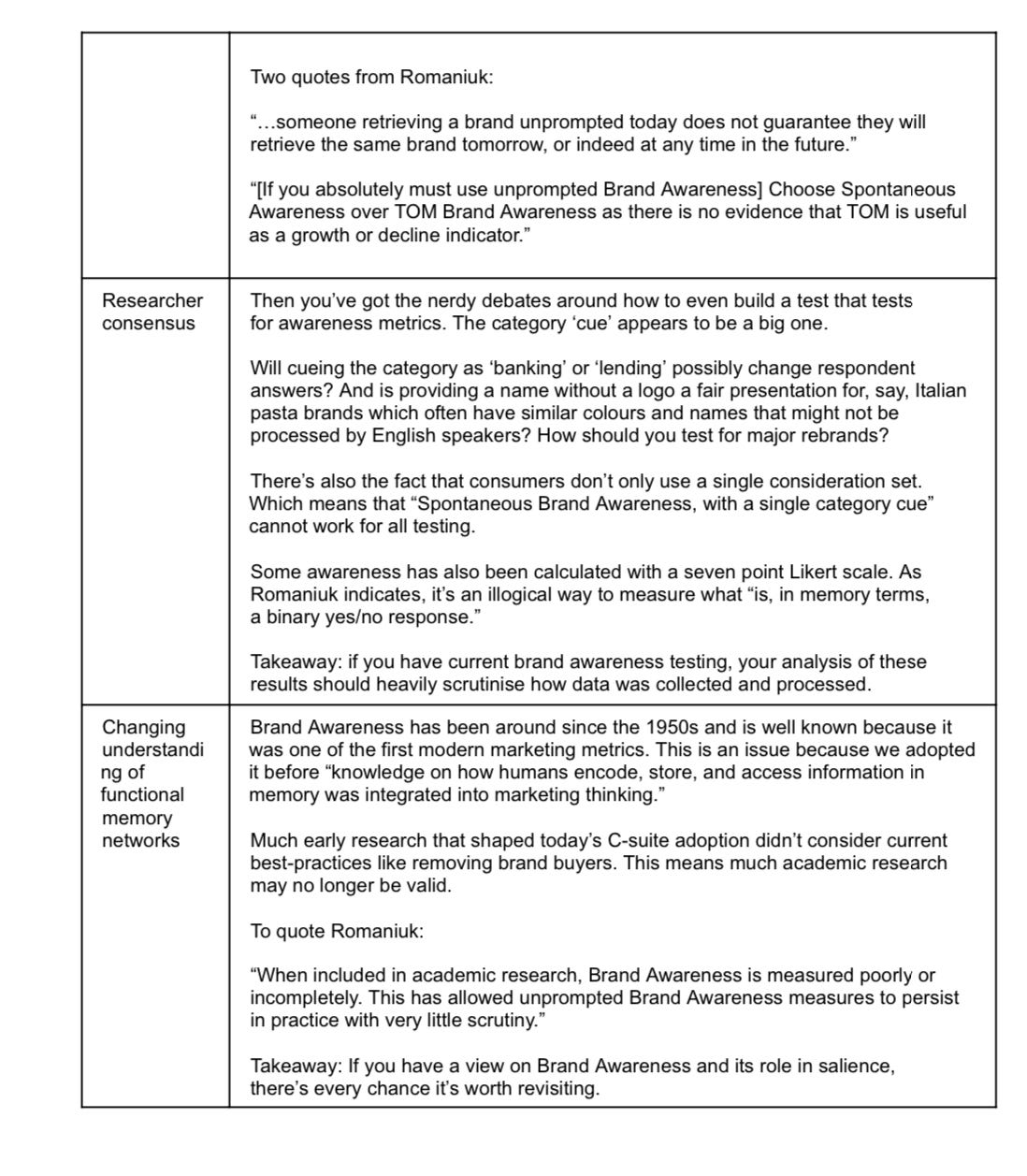

In her book, Better Brand Health, she condenses years of research into 20 pages of explanation. In my attempts to summarise (read: hubris) I have bludgeoned her analytical research into Brand Awareness’ five main failures.

But first, back to the basics of what the metric is comprised of and what those components tell us.

What constitutes Brand Awareness and what do we use it for?

Brand Awareness is made up of three main metrics.

1. General Spontaneous* (“how many podcasts can you name?”),

2. Top-of-Mind or (TOM) Spontaneous (‘what’s the first podcast that comes to mind?’):

3. Prompted/aided (“Tick all the podcasts names/brands you recognise”)

*Note: Romaniuk and others refer to this as ‘Spontaneous’, not ‘General Spontaneous’. I’ve renamed for the purposes of this article so as not to confuse it with the other unprompted awareness, ‘TOM Spontaneous’.

The first two are considered unprompted, even though we provide them with a ‘category cue’ (in this case, podcasts). The third is considered prompted as respondents are given a combination of the brand name and logo.

And what do they tell us?

Romaniuk’s definitions are italicised below:

1. Category identification: Testing if buyers are aware your brand is a member of its category.

2. Ease to retrieve: Testing how quickly buyers retrieve your brand from memory when cued with your category name. [When you say ‘soda’, they say ‘Coke’.]

The above is so simple, so basic, and so prosaic to our profession that any CMO should be able to explain it.

The problem with that is, even if they were to explain the above, they’d be missing the point that it’s largely useless. Which brings us to Brand Awareness’ five failures.

The findings of Romaniuk and others should give pause. Not only because they paint a bloody woeful picture of Brand Awareness as a metric, but because they beget questions on every measurement that follows.

After digesting the research, many of you will follow this three-point path:

1. Measurement of Brand Awareness as a metric is only useful if you’re testing a very limited range of the sub-metrics it’s built from.

2. Even if your testing follows best-practice, you need to accept that instability of memory renders your results irreplicable.

3. If Brand Awareness metrics are a flawed means for measuring brand growth, then the generic funnel flowing from ‘Consideration’ to ‘Conversion’ is defective.

With that in mind, Brand Awareness might be our industry’s most dangerous metric — especially considering it’s so well-known within corporate circles.

If what CEOs most understand of marketing measurement is an outdated Brand Awareness metric that we’re unable to prove, then there’s no wonder that budgets are increasingly redistributed to ‘performance’ media.

I know I told you where the rub lies a long way up the page, but, really, here is where it should rest.

CEOs know brand is important. They’re aware of the relationship between brand equity and pricing power and how it’s manipulated by Tesla, Apple, and the like. What they need to know is how to prove to shareholders that investing into emotional puppy-laden ads will generate revenue.

And if you’re a new CMO who tries to explain the ‘Brand = $$$’ argument using traditional Brand Awareness metrics, it won’t mean diddly squat if your campaign works or not.

After your campaign activity finishes, you’ll probably see soft metrics increase and people will be happy.

Then, the financial quarter will close and your CEO will ask why marketing ROI is low. You’ll tell them that brand takes time.

Quarters will pass and they’ll ask how much time exactly.

As you show them non revenue-based awareness indicators like spikes in ‘share of search’ they’ll become increasingly agitated.

And, finally, when revenue does start to rise, you won’t be around to see it because a ‘performance’ CMO will have taken your place.

Jaskaran Enters:

Organic social is becoming more and more about brand awareness

The struggles highlighted above by CMO Anonymous are increasing because brand awareness is being dominated by social channels. Not all but many organic social marketers are taking a strictly performative approach. There is less brand and more internet culture in the strategies and content.

Brands need to identify when they're being the butt of the joke versus being part of it. Often, chasing social media trends that aren't true to their purpose can dilutes distinctive assets, alienate OG customers, and erode their brand. When it comes to awareness, all publicity is not good publicity.

There is huge difference between brands that get big on social media by using their identity vs by honing on their identity. One exploits, One connects.

What we have seen until now has been brands using their identity to differentiate themselves from others. In order to jump on trends and do memes about their brand. I consider that as a social strategy using the brand to generate awareness. It’s a brand generating awareness but people aren’t becoming aware of brand to an extent that it impacts revenue or purchases.

Brands focusing on their identity scream ‘This is who we are’. Everything they do generates a response like ‘That’s Duolingo/Nutter Butter/Currys/RSPB for you’.

Soul-searching is a practice that most social marketers need to do, look inwards before you start searching the internet. That’s how you find that brand element that should be focus of your social strategy.

A non-social but recent example is Burberry. The brand was failing because they were using their identity, instead of focusing on it. Their outerwear campaign launched this week and it’s getting a ton of love from social audiences. Because for the first time in a while, Burberry decided to focus on the British brand identity (highlighting British outdoors and weather) instead of using it as a selling point. They said, “This is who we are.”

When social marketers are taking a strictly performative approach and CMOs are left thinking it is part of brand building. The strategic misunderstanding leaves the CMO in fault and you know what’s next. 🛫

Article you need to read this week

Did Apple Just Kill Social Apps? - NY Times

Do big and small brands need different kinds of attention? - Contagious

Everybody wants to be Beyoncé, nobody wants to be Beyoncé - Ochuko Akpovbovbo

15 Brand Strategy Case Study Examples for Designers and Strategists - Melinda Livsey

The Rise of Science Sleuths - Undark

Drowning in Strategy Resources & Struggling to Assess Quality - Baiba Matisone

The Rage of Google - Matt Stoller

The Psychology of Maximum Effectiveness - Ultra Successful

Who’s winning the marketing game this week?

Companies that are doing brand awareness are playing the long term game, because it is about creating and nurturing a relationship with your user. Of course it's hard to measure. Because conversion is not the point. In a world so driven by data, this is rarely understood. The worst and most counter-productive behavior is when campaign managers try to measure brand effort with acquisition metrics.